1916 and Lenin on Imperialist Economism Remembered and Revisited by Nickglais

Our Norwegian comrades at Tjen Folket – Serve the People recently wrote an excellent article called Politics over Economy which addressed the question of Economism and how that inhibits the struggle against Capitalism and Imperialism

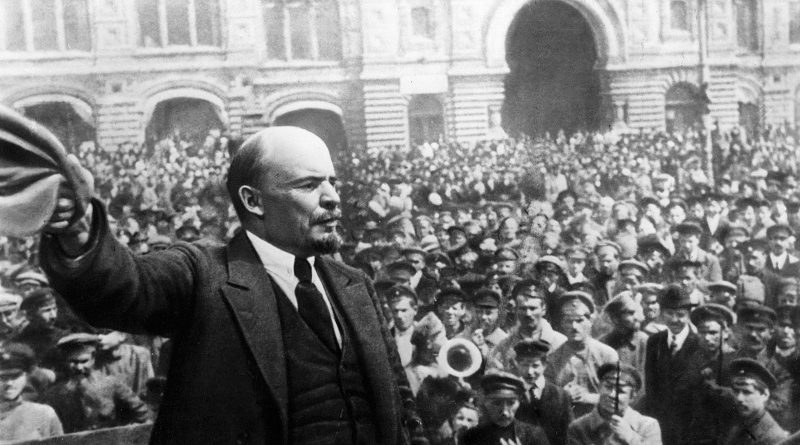

Lenin’s classic “What Is to Be Done” was written in opposition to economism.

Economism is a tendency in the workers movement that only focuses on economic struggle – struggle for wages, welfare and rights in the workplace – and that limits itself to union work.

As a resistance to this, Lenin puts forward at versatile political struggle with a much wider spectrum of resistance against the bourgeois state.

This article reminded Democracy and Class Struggle of Lenin’s Dispute with Kievsky on the National Question – in fact Norway figures large in that dispute – with Lenin firmly supporting Norwegian Independence from Sweden in his exposure of Imperialist Economism.

Lenin’s October 1916 Article ” A caricature of Marxism and Imperialist Economism” illustrates how the blinkered economist viewpoint had been extended to national struggles by Kievsky – one cannot read this 1916 article without being struck by how many of Kievsky’s mistaken ideas on the national question are present on the so called “revolutionary” left particularly in UK and USA today.

We reminded the “British” Left of their mistakes on the National Question few years ago in our article the Cosmopolitan Left and the National Question.

http://democracyandclasstruggle.blogspot.co.uk/2012/10/the-cosmopolitan-left-and-national.html

http://democracyandclasstruggle.blogspot.co.uk/2016/08/norway-politics-over-economy-by-tjen.html

LENIN ON IMPERIALIST ECONOMISM BY DOUG LORIMER

During the first imperialist world war, a trend began to emerge among the Russian revolutionary Marxists that argued that since national oppression could not be abolished without an economic revolution against imperialism and capitalism, Marxists did not need to concern themselves with the problems of a political revolution to achieve democracy.

Instead, the “nascent trend of imperialist Economism” (as Lenin characterised it) argued that all that was needed to abolish national oppression was the anti-capitalist economic revolution, i.e., the socialist revolution.

The imperialist Economists ignored the fact, as Lenin explained in his October 1916 article “A Caricature of Marxism and Imperialist Economism”, that in “all the colonies and the semi-colonies … there still exist oppressed and capitalistically underdeveloped nations” and, therefore, “Objectively, these nations still have general national tasks to accomplish, namely, democratic tasks, the tasks of overthrowing foreign oppression” in the political sphere.

Furthermore, the imperialist Economists displayed “just as complete a misinterpretation of the relationship between socialism and democracy” as the “late and unlamented Economism of 1894-1902”. Explaining what he meant by this, Lenin wrote:

All “democracy” consists in the proclamation and realisation of “rights” which under capitalism are realisable only to a very small degree and only relatively. But without the proclamation of these rights, without a struggle to introduce them now, immediately, without training the masses in the spirit of this struggle, socialism is impossible.

Having failed to understand this, Kievsky bypasses the central question, that belongs to his special subject, namely, how will we Social-Democrats abolish national oppression? He shunts the question aside with phrases about the world being “drenched in blood”, etc. (though this has no bearing on the matter under discussion). This leaves only one single argument: the socialist revolution will solve everything!

Or, the argument is sometimes advanced by people who share his views: self-determination is impossible under capitalism and superfluous under socialism.

From the theoretical standpoint that view is nonsensical, from the practical political standpoint it is chauvinistic.

It fails to appreciate the significance of democracy. For socialism is impossible without democracy because: (1) the proletariat cannot perform the socialist revolution unless it prepares for it by the struggle for democracy; (2) victorious socialism cannot consolidate its victory and bring humanity to the withering away of the state without implementing full democracy.

Source: http://links.org.au/node/132

IMPERIALIST ECONOMISM BY DESMOND GREAVES

Connolly had no great difficulty in convincing his comrades in Ireland of the need to combine their proletarian demands with the all-important democratic demand of national liberation.

He found it less easy to convert English Socialists, who confused the growing fraternity of the peoples in the struggle against imperialism with the abolition of the state boundaries established by imperialism for the purpose of exploitation.

To this day there survive sincere Socialists of the old school who are confused enough to believe that the Irish should withdraw their demand for independence in the interests of internationalism.

There are some who fondly imagine that the international unity of the workers of Europe will be strengthened as a result of the Common Market. It is as much as to say we will be united provided we are all put in the one prison.

The classical centre of this argument was Poland. Lenin called it “imperialist economism”. Economism, as you will remember, was the doctrine that it was sufficient for a workers’ party to prefer proletarian demands, and that democratic demands were not their business.

Lenin re-plied that this was to leave the stuff of politics to the bourgeoisie. In the same way, to refuse to challenge the frontiers established for and on be-half of landlords and capitalists, where they conflicted with the wishes of the people, was to leave vital questions affecting the lives of the millions to be decided by imperialism.

It is remarkable that such splendid characters as Rosa Luxemburg should have been associated with this recrudescence of Proudhonism.

The controversy continued over nearly twenty years, and it was against this background that Joseph Stalin drew up his celebrated theses on the National and Colonial Question, and Lenin conducted some of his most profound and thought challenging polemics, which continued until that stage of the First World War when theories could be tested in practice.

The theses of Stalin on Marxism and the National Question were concerned not so much to refute imperialist economism or the new Proudhonism, as to answer the Austro-Marxists who were trying to divorce nationality from territory of residence.

These had made the fantastic proposal that members of the various nationalities inhabiting the Austro-Hungarian Empire should register the nationality they belonged to, and have the right to elect a national council, irrespective of their place of residence, which could then conduct “the cultural affairs of the nation”. Stalin showed that the main concern of these opportunists was to frame a national policy which would not upset the political integrity of the Empire, and could so leave the essence of national oppression untouched.

In the course of his refutation of National Cultural autonomy, Stalin was obliged to attempt a definition of a nation, which he described as:

“…a historically evolved, stable community of people formed on the basis of a common language, economic life and psychological make-up manifested in a community of culture.”

Stalin emphasised that it was sufficient for a single one of these characteristics to be absent to disqualify a community from the title of nation. The national policy of Bolshevism was based on the right of self-determination of nations, which was meaningless without the right of territorial secession. At the same time the exercise or non-exercise of that right was a matter for the nation to decide in the light of circumstances, the paramount consideration being of course the question of class interests.

The work of Stalin on the national question was a powerful contribution to Marxist thought and stood the test of practice in the revolutionary period that followed to a remarkable degree.

Less than a year after the Easter Rising came the collapse of Czarism in Russia. The general principles of Bolshevik national policy were enshrined in the slogan for a peace “without annexations or indemnities “. Lenin explained carefully that this meant the undoing of old as well as new annexations; it meant England’s evacuating Ireland as well as Germany’s getting out of Belgium.

And it is interesting to note the difference be-tween Lenin’s approach and that of President Wilson’s, whose embellishment of the imperialist war was typified in his notorious fourteen points. At the peace conference it was agreed that no nation seeking in-dependence should be heard unless Britain, France and the USA unanimously agreed to listen. On this basis both Irish and Egyptian claims were vetoed.

A glance at Stalin’s strict conditions will show that it could be a subject for considerable debate as to whether this people or that possessed all the qualifications of nationality. Was a people to be denied the coveted prize of independence because it could not convince an international jury that it was a nation in the full sense of the word? Who was to decide? Lenin’s reply was that in case of difficulty the people themselves decided if they were a nation or not. He put it this way:

“The theoretical definition of annexation involves the conception of an ‘alien’ people. ie a people that has preserved its peculiarities and its will for independent existence.”

He adds that the slogan must be “taken as inseparably connected with the proletarian revolution. Only in connection with the revolution is it true and useful.”

This was in May 1917, and the Bolsheviks were pointing out that an imperialist peace could only be an exchange of annexations. Of course, one should note that this presumes other things equal. As Lenin frequently pointed out, every democratic principle is open to abuse.

I doubt whether English Socialists would accept the secession of Cornwall from a Socialist England after the United States had occupied it and secured a separatist majority while its troops were still there. Certainly the Irish will not accept an English-concocted nationality for Ulster. But the refusal to accept the abuse of a principle does not vitiate the principle. And on that principle the Bolsheviks acted and permitted secessions which involved future military risks.

Perhaps I should add one thing about the Stalin theses. It is a criticism which he made himself. In 1925, criticising Semich for underestimating the importance of the right of secession, he notes that Semich quotes from Stalin’s theses the passage “The national question is a struggle of the bourgeois classes among themselves.” He comments:

“Stalin’s pamphlet was written before the imperialist war, at the time when the national question had not yet assumed world-wide significance in the eyes of Marxists, and when the basic demands concerning the right to self-determination were considered to be, not a part of the proletarian revolution, but a part of the bourgeois-democratic revolution. It would be absurd to ig-nore the fact that since then a fundamental change has taken place in the international situation, that the war on the one hand and the October revolu-tion in Russia on the other has converted the national question from being a particle of the bourgeois-democratic revolution into a particle of the proletar-ian-socialist revolution.”

Would we be wrong in saying that in respect of this question, Connolly anticipated the Bolsheviks, noting the beginnings of the change in 1894 and showing his grasp of it the moment the imperialist war broke out?

And may we not think that the Easter Rising in Ireland, which Lenin used as a test of the validity of his theses on national self-determination written earlier in 1916, was an important contributory factor in rendering Bolshevik thought more precise, just as the Fenian Rising had stimulated Marx?

One of Lenin’s main points of emphasis was that imperialism had divided the world thanks to the corruption of a small section of the proletariat into two opposing camps, workers in the imperialist countries, a corruption which might of course ideologically affect the majority. We discern it in the two world trade union movements of to-day.

It is still true that a people which oppresses another forges its own chains.

This is the great significance of the national liberation struggle for the British working class.

Source: http://www.connollyassociation.org.uk/desmond-greaves/the-national-question/