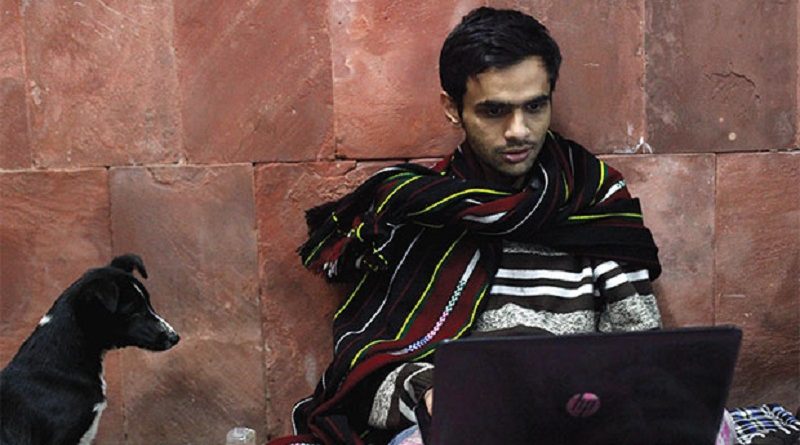

India : A Year of The Student Revolts – Umar Khalid Looks Back At 2016

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair”

These opening lines of Charles Dickens’ classic novel “Tale of Two Cities” were written for a different time and space. But carefully read, these timeless words also capture the depiction of 2016 the year of the widespread students’ movements. Wisdom, Foolishness, Belief, Incredulity, Light, Darkness, Hope, Despair– it had it all round the year, and in plenty. It was not a year that allowed us a moment of relief, and conversely it could also be said we didn’t provide the rulers with any either.

I. Season of Light, Spring of Hope

As I sit down to pen down my thoughts on the year gone by on an extremely chilly last winter night of the year, I can’t help but be reminded of another chilly winter night in the early days of the year . It was the night of 17th January 2016. In JNU, students across several organisations had planned a campaign in solidarity with the socially boycotted dalit research scholars of the University of Hyderabad. We had only begun the campaign when someone shrieked from behind with the terrible news that RohithVemula – one of the five punished students – had hanged himself. The chill that descended that night had thickened. It engulfed all of us, but there was no gloom. There was instead simmering anger. Someone raised her fist with the slogan “This is no suicide, this is murder”.

Students across the country all through 2015 – from FTII to Occupy UGC – had been in the middle of extremely intense battles against the government. Rohith’s institutional murder in the beginning of 2016 took the movement to another level altogether. The Brahmanical core of the government had been laid bare, it stared us in the face, its rotten stench was all around. This was the moment to confront, clean and isolate it.A time to initiate our own Swach Bharat Campaign – cleansing the country of caste and Hindutva.Over the next few weeks, water cannons, police detentions and lathis proved completely ineffective in quelling the students’ rebellion that had erupted.

Around 20 days later, some of us in JNU organized a program on Kashmir on 9th February. On this day, three years back Afzal Guru after being put through what several human rights activists termed as a sham of a trial was secretly hanged ostensibly to satisfy the collective conscience of the society. To quote Milan Kundera, the history of people against power is the history of memory against forgetting. At this juncture of the students’ rebellion, it was all the more important to talk about the lesser talked about injusticesthat have also shaped the times we live in.

But if Rohith, by talking about caste, had touched the soft spot of Hindutva, we by talking about Kashmir disturbed its raw nerve. And in absolutely no time the wrath of the state and the society was unleashed upon some of us. By society here, I mean the dominant viewpoint and morality in the society, and the two – state and society – seem to have eerily merged today. As shrill anchors took upon themselves the twin task of being the judge and the lynch-mob simultaneously and rescue the political and moral crisis the government found itself in after Rohith’s death, facts became difficult to distinguish from third grade pulp fiction.

II. The Age of Foolishness

One of these days, a TV anchor with extreme authority called me out as a Jaish-e-Mohammad terrorist who had been to Pakistan. I was in hiding, and if not for the extremely dangerous ramifications of this assertion, I would havelaughed at it. I had already laughed at many junctures during the famous Times Now show where I was branded as anti-national by no one less than the judge, jury, prosecutor Arnab Goswami himself. On that night, instead I re-read the suicide note of Rohith Vemula. The brilliance of that small yet haunting note is that it leaves you with a new insight everytime. In those moments, I realized with first-hand experience what it meant to be reduced to your immediate identity. My belief or lack of it in religion was immaterial, what mattered solely was the identity in which I was born.

One any other juncture, having your son in the custody of the police would throw parents in extreme anguish. But in the paradoxical times that we live in, my mother later told me that the day I was arrested by the police was the first day she slept in peace. At least she know that I was alive and where I was. In the previous few days, she had imagined the worst.Was I already in police custody and being tortured? Would the BJP do to me what they did to IshratJahan in Gujarat? I can never forgethow my 80 year old grandfather hugged me after I returned from jail and broke down. It is the only time I have seen him in tears and shivering. In that moment, as I hugged him, I thought about predicament of the families of Ishrat Jahan, Atif, Sajid and so many other Muslims who have been killed, tortured, framed, damnedand jailed simply for their crime of bearing a Muslim name. RohithVemula’s words of what it means to be reduced to your immediate identity, apart from others, would strike a chord with so many young Muslim men and women in this country. Every person with a Muslim name is a suspect, an anti-national by virtue of her/his name.Moreover, by uttering the seditious K word I had committed an additional, or rather the ultimate sin.

The idea of the attack on JNU was to divert the attention away from Rohith and crush the student rebellion. It not only failedmiserably but through its own actions the BJP itself ensured that the students’ movement became a country-wide phenomenon. The arsenal deployed by the RSS and BJP – of creating a televised spectacle of this witch-hunt – ensured solidarity of students across universities. Will someone tell the NewsX anchor who was accusing me of conspiring to organize programs similar to the 9th February program in 17-18 universities, that it wasn’t me but him and his ilk that ensured this solidarity. Students were now not only talking about the attack on them, but also the injustices elsewhere from Honda workers, Bastar to Kashmir. The students’ movement, as Comrade Anirban declared in his speech after return from jail, had in those moments effectively become the extra-parliamentary opposition. Much more potent than any parliamentary opposition had ever been and Rohith Vemula was the symbol of our rebellion.

III. The Season of Darkness

There were joyous celebrations of thousands in JNU as first Kanhaiya, and then Anirbanand mecame out from jail. Even the 16 day long hunger strike in the scorching heat of April and May was more of a carnival of fighting an adversary that was already delegitimized. But once the witch-hunt that began in February was over, where the government had committed several tactical blunders in the beginning itself, the fight was only going to enter into a newer and more difficult phase. None of us were in any illusion about that. We had forged newer solidarities but with an enemy as unscrupulous as the RSS it was only a matter of time before the counter-attack began. The shift of MHRD portfolio from an inept Smriti Irani to the shakha trained Prakash Javadekargave certain indicators of the times to come. As the former environmental minister, he had an unblemished record of ensuring 100 per cent clearances for big corporations without any legal hassles or political hue and cry. A similar strategy had to be replicated in the universities.

As the new semester began in July, we witnessed thisshift in the new modus operandi of the sangh appointed VC. The democratic institutions, rules and procedures within the university that pose a threat to the imposition of the sangh’s project are all being cavalierly subverted and hollowed outfrom within. JNU’s lively culture of debate and discussions is being attacked by simply banning meetings and criminalizing protests. Rather than sending students to jail and making martyrs out of them, the wiser option for the government through its hireling administrationis now to keep threatening them with one enquiry after the other and to trap them in lengthy legal proceedings.

The effort is, as a faculty member recently described in an opinion piece, to ensure the slow death of a vibrant public institution. Today our VC feels no need to hide his political partisanship. For example, just on the eve of JNUSU elections, he handed down his verdict regarding the students’ appeals on HLEC reaffirming the punishment to 20 prominent left activists. The intention was clear – by punishing the left activists, he wanted to keep them out of the elections as per the new guidelines of students’ union elections, and thereby help the right-wing. Can you believe it, the head of the institution himself directly intervening to help the ABVP win in students’ union? And, why not? Both owe their loyalty to Nagpur, and work through each other. Even after his best efforts could not ensure their victory, the VC closely works with these hooligans who can be seen every single day at the administrative block – playing the role of informers, henchmen and foot soldiers of the regime.

IV. The Winter of Despair

Many people, especially outside Delhi, only recall the events of February and March when talking about the attack on JNU. But for those of us studying and living in JNU, thesangh’s attack never really abated. Their agenda is clear – to bull doze the sangh’s pro-corporate, Brahmanical Hindutva-wadi policies in higher education. Anand Teltumbde in an article last year had quipped that was business as usual for the previous government – ensuring exclusion of education from deprived backgrounds by selling it off to the highest bidder – is also a deeply ideological project for the present ruling dispensation. The codes of Manu prescribe a set role for everyone in the society, and today combined with the assault of market it has become a deadly cocktail for students coming from deprived backgrounds, oppressed castes and religious minorities in universities. The effort, now by the present day progeny of Manu, is to push them out, if need be violently.

As another winter set in,they chose one of the most vulnerable, helpless target in JNUto once again put into effect this agenda. A new student coming from the Muslim community, who was not only coping up with the travails of being in a new space but hardly had any friends was surrounded, beaten up, abuse on communal lines and threatened of being killed.

Manufactured communal frenzy is quite common in our country on the eve of elections but to think of communal frenzy in JNU during elections to hostel committee elections was unthinkable. And if we thought Dadri was far away, we almost had another Dadri right in our university as ABVP goons ferociously bellowed to ‘send him to 72 virgins’ while beating him up. We don’t know where they eventually sent him, since from the next morning he was never seen.

The assault on Najeeb was not just madness, there was a method to it.It had to serve as a reminder to others from his community of what could await themif they dreamed ofpursuing higher education. They should not even dare to think out of their ghettoized Even as I write this, 11 students from marginalized backgrounds have been summarily suspended from JNU for their crime of demanding that admission policy be changed so as to make it socially just and inclusive. The action on them is a clear signal by the brahminical forces that dissent and any attempt to ensure social justice and equality are not to be tolerated in this fascist regime the edifice of it isBrahminism.

Fascism and disappearances have a long history – from Chile to Kashmir. Disappearances are one of the most agonizing things to cope up with – you remain in eternal wait and dread even at thought of losing hope. But hope – the hope of waiting for your loved ones to return – is what engulfs and eats you up from within. You want that wait to end, knowing very well that it is hardly in our capacity to do anything about it. Place yourselves in Najeeb’s mothers’ and brothers’ shoes and think of something similar happening to someone close to you.

Even as student activists who had been active in the campus for years, this was an entirely new phenomenon. We had fought against arrests, even killings and riots. In each of these instances, there was a clear road map for struggle. But here, in this case, we were totally ill-prepared with no no manual from the past to follow. Even though you knew who was behind it all and with whose complicity, you ended up going to the very same people for justice. We, who had been enraged at the news of Delhi police carrying out raids in the campus in February were now demanding the same Delhi Police to carry out combing operations in the campus. The ABVP which had zealously supported the raids in February, now protested against what it called the ‘militarization’ of the campus at the behest of the left. The world had turned upside down.

The first few days after Najeeb’s disappearance saw thousands pouring out on the streets once again. It was as if the spirit of February had been re-ignited. But as days and months passed by, not only the mobilization within the campus but even that of democratic sections outside receded. Even atrocious acts of the authorities – the police planting false news in the media to profile Najeeb as mentally deranged or the JNU administration providing complete impunity failed to cause much outrage. Difficult questions began to be posed.

How was it that the events in February-March were perceived as an attack on the university, but the enforced disappearance of Najeeb was just an attack on an individual? Why was it that the JNUTA, which played such a phenomenal role during February-March in standing by the students was so half-hearted in its response this time around? Did it have to do with this shift in strategy of the sangh – no more spectacle spectacle through vicious media trials but a quiet imposition of their agenda? Or did it reveal some fault-lines within the progressive camp? Was it to do with Muslim’s identity? Why else would JNUTA insist that for them Najeeb was just a common student, and his religious identity was simply immaterial? Did it also not matter for those who attacked him? Is it the same thing to say that we will stand with every student irrespective of her/his religion and to overlook the specifities of the nature of the attacks today? In such a case, whom does this flattened secular narrative help? Moreover, is it really a secular democracy that we are living in?

V. It was the best of times, It was the worst of times

From Rohith to Najeeb via the crackdown in February, the students revolt of 2016 have posed many of these and other questions – about caste, gender, religion and class; secularism and democracy;or the centrality of Ambedkar to Marxist praxis today. None of these have easy or straightforward answers. But, these are the most crucial questions that the students’ revolt of 2016 have thrown up – something the hacks sitting in the Communist party leadership also need to pay attention to and learn from. May be, in the face of this repression, or most likely because of it, something new is being born.We have not just fought the powers that be, but also put our minds through some of the most crucial of recent times. In this fight against capitalism and Brahmanism, we are fighting to win but even defeat is not entirely out of the realms of possibility in this extremely uneven battle. But even if we are defeated in the short term, the ideas brought to fore by the students’ revolt of 2016 holds the key to the victory of tomorrow. With huge odds stacked against us, we are not ready to give into pessimism. The year 2017 is going to be an exciting one – another one at the barricades.

Jai Bhim Lal Salaam!

Umar Khalid

Bhagat Singh Ambedkar Students Organisation

Source : http://www.indiaresists.com/a-year-of-the-student-revolts-umar-khalid-looks-back-at-2016/