Bastar Journalist gives Adivasis a Voice

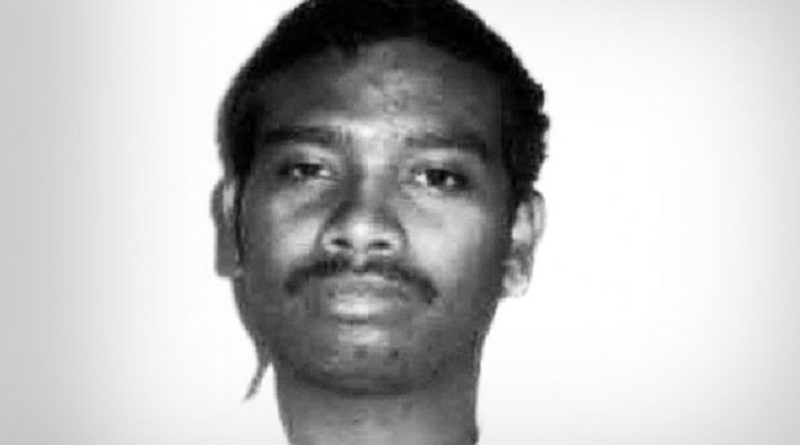

He was warned repeatedly by the police, even detained and stripped, but Bastar journalist Santosh Yadav continued to report from its villages, giving voice to adivasis who had been molested by the security forces during raids, as well as to families of adivasis killed in so-called encounters all in the name of the “war against Maoists”.

But Yadav didn’t just report; he brought these victims to JAGLAG (Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group) so that they could get redressal in court.

In September 2015, Yadav was arrested and charged with murder and being present in an “encounter” in which one jawan was killed by Maoists. The Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act were used against him.

Out on bail after 17 months of imprisonment, Yadav is back to doing what he loves: reporting from Bastar’s interiors. Of the two Hindi newspapers for whom he wrote, one has told him to lay off Naxalite stories, while the other, a local paper called Chhattisgarh, has asked him to keep writing. He has also done a videography course and hopes to send news through the website CGNet Swara to mainstream news channels.

His parents and wife are at their wits’ end, he admits. Why then does he continue to risk his well-being? “I have to die some day; may as well do something I want to,” smiles Yadav, who addressed a public meeting in Mumbai on Saturday organised by the Bastar Solidarity Group.

The 32-year-old smiles a lot but is candid about how much he and his fellow inmates cried in jail. “The adivasis I had tried to release wept when they saw me brought to jail. There was a doctor inside, too, on the charge of helping Maoists. He and I would lament our fate after every family visit. It became so bad that we had to warn each other not to cry!” Yadav took to journalism for two reasons: he loved writing, and he wanted to bring to light the reality of his region. His father and brother earned just enough to sustain the family, and he earned occasionally by getting advertisements on commission. But reporting remained his fulltime profession.

He started off by writing about the pitiable conditions of roads, government hostels, about adivasis students being forced to work, before venturing into the villages.

“Some adivasis I met there would land up at my house and request me to inquire with the police about their menfolk, who had been picked up randomly.” That’s when the police started warning him not to get involved. But says Yadav, “I never wrote a report without getting the police version. It was only when I found that they refused to release obviously innocent adivasis that I started taking the families to JAGLAG. How could I not have done this? It would have been like seeing someone fallen on the road and not helping.”

In prison too, Yadav couldn’t help but protest when he saw how narcotics and medicines were being sold by senior inmates in connivance with jailers, and how facilities for the education of prisoners were denied. He organised the inmates and they went on a hunger strike on Gandhi Jayanti last year. Predictably, they were lathi charged. Yadav was singled out till he lost consciousness. He was then stripped and put into solitary confinement and finally, transferred to another jail.

Yadav feels “more sad than angry” at the way Bastar is projected by most news channels. “They don’t show the truth. They harp on Maoists picking up the gun. But who makes adivasis into Maoists? If the security forces molest and even rape adivasis, kill innocents in fake encounters – what will their families do? Is there no law for security forces? Has the government given them guns and immunity?”

Source: http://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/other/bastar-journalist-gives-adivasis-a-voice/articleshow/60053662.cms